Thursday 26 March 2020

PPE in action but only one pair of gloves and exposed facial skin (courtesy Eugeneonline)

Barely a day goes by at the moment, without me hearing of another medical colleague who has perished at the frontline of Covid-19. Each was in their prime. Researchers from around the world have been looking at this, and why healthcare workers should be so exposed. For example, by 24 February 2020, 2055 healthcare workers in China had been infected and 22 had died. Ninety percent of those infected had come from Hubei Province. The infection rate of healthcare workers for Covid-19 (2.7%) was lower than for SARS (21.1%). The Chinese concluded that the most likely cause of death was inadequate personal protection.

In the early days of Covid-19, healthcare workers did not fully understand the problem and so perhaps did not adhere to their personal protection as strictly as they would now. Viral load was also an issue. Long-term exposure to large numbers of infected patients increased the risk of infection. The pressure of work also exhausted healthcare workers, who were more likely to make errors. Another problem was a shortage of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), about which we are hearing so much at the moment.

Data from Italy show that 9% of cases are healthcare workers, again thought to be related to a lack of PPE. Some put this figure as high as 20% and a colleague of mine in northern Italy said that 11% of the patients on his hospital’s intensive care unit were healthcare workers with Covid-19. In his country, to date the virus has infected more than 5000 doctors and other healthcare employees, most of whom were on the northern frontline.

Forty-one Italian health workers have so far died. One of them was Dr Roberto Stella who, at 67 years of age, was the President of the Medical Guild of Varese and who apparently continued to treat patients even when protective gear ran out. His death highlights the importance of PPE and why the UK medics are not making a fuss when they say they need more and better protection.

Roberto Stella – sadly he did not make it

The problem with PPE is not only whether it is available but, when it is, how you put it on (don), how you take it off (doff), and what you do with it when it is being worn. There are different types of PPE and much debate as to what design is the best. One might opt for a full body suit, which gives maximum protection. Believe me, that is my choice even if it is a nightmare to wear. Once it is on, it is on. Fancy a pee? Bad luck. Just hang on to the end of your shift.

Alternatively, you can opt for no protection at all. That may be very comfortable, but it will not take you long to become infected. Or, you might consider a halfway house and there are many different choices. Hat, mask, gloves and apron; hood, goggles, mask and gloves; wellies, hat, gloves and visor. You name it and it has been tried.

For surgery I would normally use a wrap-around gown, a visor and hood, wellies and double gloving. My innermost pair of gloves is coloured green, so I instantly know if I have accidentally penetrated the outer pair and can immediately change them. Time was I would wear Kevlar gloves, for maximum protection, but I do that less often now as they make it difficult for my fingers to feel. There is a lot of feeling in surgery.

Researchers looked into the use of PPE after the Ebola and SARS epidemics, to see which design was the most effective, the best way to remove it, and how to ensure that healthcare workers used the PPE as instructed. Although the researchers’ data were low quality, they concluded that gowns were better against contamination than aprons, and that a powered air-purifying respirator protected better than none. Double gloving led to less contamination than single gloving and more breathable materials did not lead to more contamination but were more comfortable for the user.

Face-to-face training in how to don and doff PPE is essential. Video training is not so good. The critical moment seems to be the doffing, when contamination of the wearer is common. Should this happen, contaminant can reach the health worker’s personal clothing, and from there right into their system.

Donning and doffing PPE has thus become an artform. It is not a matter of turning up to work, whipping on the PPE, getting on with it, and wriggling it off at the end of the day. There is a carefully rehearsed system to follow. Donning is undertaken in the correct order and under the eagle eye of a trained observer. Once donned, the PPE should not be adjusted during patient care and gloved hands should be frequently disinfected. Doffing is high risk, again with a stepwise procedure and under the eye of a trained observer. Doffing is the key moment of danger.

There are different versions of PPE for healthcare workers. Any given outfit is referred to as an “ensemble”. The Health and Safety Executive evaluated different ensembles that were being considered for the assessment of a patient with a suspected High-Consequence Infectious Disease (HCID). The study concluded that a basic-level PPE ensemble such as a visor, gloves and apron, did not afford adequate protection in a clinical HCID scenario.

Does this PPE look effective to you? (courtesy Stephen Brashear/EPA-EFE-Shutterstock)

Key differences between the various ensembles depended on whether they consisted of a gown or coverall, hood or surgical cap, wellies or boot covers. Key weaknesses included some ensembles leaving areas of skin exposed, for example wearing a surgical cap rather than a hood.

Fluid from a cough, or even vomit, might penetrate the gown material of the sleeve. In surgery I always use impermeable sleeves to avoid this. In my case I do not want blood to penetrate my gown. In the case of Covid-19 it is secretions of some sort, or blood.

It is also possible for a gap to develop between the bottom of a gown and the top of wellies, so that liquid can drop into the boots, especially if a patient vomits. It is very exposed being a healthcare worker dealing with an HCID, as risks come at you from all angles. You can perform perfectly all day. All it takes is one error.

Doffing boot covers, if you wear them, can also be dangerous as it is common to have accidental lower-leg contamination. Facemasks, too, if they are not worn properly, can easily allow bugs in round their margins. Next stop you are on intensive care as a patient, not as a member of staff. PPE is thus critical, whatever design is chosen. And no, healthcare staff are not making a fuss.

Away from PPE, I was pleased to learn that Dyson has been awarded the contract to make ventilators for the NHS. Somehow, I feel confident when Dyson does things and I will wager the company will do the job in double-quick time and have a snazzy design. When my turn comes to be on intensive care, can I have a Dyson ventilator, please? I understand the company is intending to make the things in an old aircraft hangar in Wiltshire that was used to pack parachutes in World War Two.

The reality of this pandemic amplified today when I saw a video of the Excel Centre in East London, which is being refashioned to take 4000 beds and two morgues. The same is being repeated in other parts of the country and Birmingham Airport is also becoming a morgue. There is no doubt the Government means business. This is just as well as the hospitals are already working overtime and I now hear ambulance sirens from my window more or less continually.

A colleague contacted me from one of the London teaching hospitals today to say that the anaesthetists had been redeployed and most of the operating theatres had been converted to intensive care units. Did I have any suggestion as to how it might be possible for a surgeon to perform an emergency operation without an anaesthetist being available? It so happened that I did, and I have passed that across. What many forget during these chaotic times is that normal work continues. People still fall over and break their legs, cut themselves, develop tummy aches, have heart attacks and are generally assaulted by Nature. Not everything a doctor sees at the moment is Covid-19.

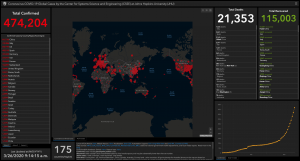

The situation this morning – 26 March 2020 (courtesy Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University)

On the positive side, if there is such a thing these days, the Czech Republic has launched an appeal to save 1,305,552 pints of craft beer from going off if it is not drunk within weeks. The beer is languishing in 32 craft breweries across the country. Although all pubs and restaurants are closed to the public, they can serve through hatches, and customers can also buy directly from the breweries. Anyone fancy a quick dash to the Czech Republic?