Monday 6 July 2020

Chronic fatigue is likely after Covid-19 (Andrea Piacquadio from Pexels)

When Covid-19 first appeared, all the discussion was respiratory. The chances were, if you caught the bug, you might make it through in one piece. If you were old or had some debilitating disease, your odds went down. If you were male, or had blood group A, you would do worse than blood-group-O ladies, but the chit-chat was largely about lungs. The world talked ventilators and oxygen, as if there was nothing else to consider.

Then in came the loss of taste or smell as an extra symptom, and slowly society realised there was more to Covid-19 then a simple respiratory illness. Some folk took forever to recover and began to show symptoms that did not match a severe pneumonia. The UK Government then opened the Seacole Centre at Headley Court in Surrey, specifically to rehabilitate patients after Covid-19. It was the first of its kind in England.

The NHS Seacole Centre dedicated to rehab after Covid-19

When the Seacole Centre opened, the NHS Chief Executive, Sir Simon Stevens said:

“While our country is now emerging from the initial peak of coronavirus, we’re now seeing a substantial new need for rehab and aftercare for Covid patients who’ve come through this terrible illness…Some may need care for tracheostomy wounds, ongoing therapy to recover heart, lung and muscle function, psychological treatment for post-intensive care syndrome and cognitive impairment, while others may need social care support for their everyday needs like washing and dressing.”

The Seacole Centre was followed by the creation of an online specialist rehabilitation service for those who have longer term problems with breathing, mental health, and other complications from Covid-19. This was yet another facility to deal with the longer-term effects of this bug.

Those who closely followed Boris Johnson’s descent into, and recovery from, Covid-19 will recall the Prime Minister puffing and panting at his lectern during the evening Downing Street briefing once he had been discharged from hospital. He was living evidence, seen on the nation’s screens, that Covid-19 and its symptoms may not disappear in five minutes.

However, with Covid-19 still being new to the world, it is difficult to predict its long-term outcome, although it is possible to make a good guess, especially if one looks at the first SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) pandemic in 2003. Then, too, patients over the age of 60 years did badly. A study from Hong Kong in 2010 looked at 55 patients for two years after that initial SARS infection. Of the 55, it turned out that 27 were healthcare workers. The researchers found that there was significant impairment in lung function, exercise capacity and overall health as a result of SARS infection a long time after the initial disease. These effects were definitely worse in healthcare workers.

Again from Hong Kong, in a study undertaken a year earlier, researchers looked at 369 SARS survivors approximately three-and-a-half years after their disease. They found that more than 40% had an active psychiatric illness and the same number had chronic fatigue. Once again, healthcare workers did badly. The reasonable conclusion from these earlier SARS studies is that victims of today’s Covid-19 may also show longer-term effects. Chronic, post-viral fatigue, and many other after-effects, are highly likely.

Sticking with the lung, it appears that some patients will be left with chronic pulmonary conditions as a result of their Covid-19 infection. Respiratory physicians call this post-Covid lung. The predominant pattern of lung lesions in Covid-19, when seen at post-mortem, is similar to that seen in the earlier form of SARS, and also in Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) coronavirus infections.

There is also a condition called post-intensive care syndrome. Although an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) can be critical to the survival of a patient with Covid-19, once the acute treatment is over, patients may have a combination of physical, cognitive and psychiatric impairment. These can include weakness and malnutrition, decreased memory and decreased attention span, as well as diminished mental sharpness and a reduced ability to solve problems. Being a patient on Intensive Care is not an easy option.

There is increasing evidence that SARS-CoV-2 can also affect the neurological system. So much so that I will dedicate a later entry entirely to this. Covid-19 certainly affects the brain stem. This is a critical part of the brain, sited just before it connects to the top end of the spinal cord. Breathing is controlled from there. A research team from Wuhan (China) and Phoenix (USA) reported on a group of 214 patients with Covid-19, in whom 36.4% had neurological symptoms. This figure rose even higher in the presence of severe disease. Problems with breathing may not only be caused by the presence of a Covid-19 pneumonia, but also by damage to the brain’s system of breathing control.

Looking at neurology, research from Strasbourg (France) was published in the New England Journal of Medicine (a seriously important journal) and showed that 67% of their patients on intensive care had signs of neurological damage. That is a huge percentage. Even when the patients went home, 33% of them had residual neurological symptoms. Watch that space when it comes to neurology. There will be plenty more to follow.

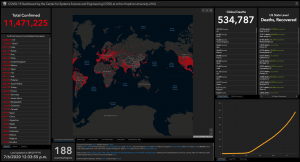

The situation this morning – 6 July 2020 (courtesy Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University)

The heart also does not escape. In the early days of the pandemic, researchers in Wuhan reported on 416 hospitalised patients with Covid-19 and found that 82 (19.7%) of them had cardiac injury. Understandably, those with cardiac injury had a higher chance (51.2%) of dying than those without (4.5%). Acute cardiac injurycan be seen in patients without any previous history of heart problems. Indeed, the UK’s National Institute for Health & Care Excellence (NICE) has published a guideline on this. No one as yet seems to know what the long-term implications of these cardiac changes may be, but it is likely there will be problems ahead. Researchers from the USA summarised this as follows:

“Lessons from the previous coronavirus and influenza epidemics suggest that viral infections can trigger acute coronary syndromes, arrhythmias, and…exacerbation of heart failure…Coronavirus disease 2019 may either induce new cardiac pathologies and/or exacerbate underlying cardiovascular diseases. The severity, extent, and short-term vs long-term cardiovascular effects of COVID-19…are subject to close scrutiny and investigation.”

Covid-19 can also damage the liver, and a study from Shanghai has described this well. The researchers there found that one-third of patients admitted to hospital with Covid-19 had abnormal liver function. This was naturally associated with a longer hospital stay. However, some of these patients had received medications with known side-effects on the liver. Consequently, how much of the liver damage was created by Covid-19 and how much by treatment was difficult to say but there was no doubt harm was done. What is also apparent is that patients who have liver disease before they acquire Covid-19 do not do well. Those with cirrhosis have a 40% chance of dying.

Lungs, nerves, heart and liver are only a beginning. Evidence now shows that Covid-19 also affects the kidney, so much so that NICE has produced yet another guideline on how to handle it. Early reports from China suggested that up to 30% of patients can develop kidney injury from Covid-19 and some sufferers have required dialysis. A more recent study from New York puts the incidence of acute kidney disease even higher, at 36.6%. The worse the attack of Covid-19, the more likely the kidneys will be injured. In the days of SARS-CoV and MERS, the kidneys were certainly affected, with 5-15% of patients ending up with acute kidney injury, which led to a death rate of 60-90%.

“Happy hypoxia” is another mystery that is baffling medics, as it seems completely illogical. Normally, a healthy person should have an oxygen saturation of their arterial blood of at least 95%. Yet sometimes, patients have attended hospital Accident and Emergency Departments with oxygen saturations much lower than this, even around 50%, although the patient feels comfortable and looks fine. The only thing wrong is an abnormal reading on a pulse oximeter, which is a small device that allows a rapid read-out of a patient’s oxygen saturation. Mine happens to be 97% at the moment, as I have a pulse oximeter on my desk, so I am alive, and not hypoxic.

Gastrointestinal symptoms can also feature in Covid-19 and have been reported in more than 20% of patients. The symptoms include nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and abdominal pain but are not said to increase the chances of death. Sometimes it is possible to have gastrointestinal symptoms but no respiratory symptoms at all. What the long-term effects may be are difficult at this stage to predict.

Covid-19 also causes numerous blood clots, frequently tiny, and especially in the lungs. The European Respiratory Journal recently undertook a large review of the problem in a paper with the title, “Thrombosis and COVID-19 pneumonia: the clot thickens!” Had I been the editor I would have changed that title. All the same, it is a good review. Research from The Netherlands has suggested that up to 49% of patients on their intensive care units developed some sort of blood clotting event. Covid-19 is so much more than straightforward pneumonia.

We must not forget the skin, which can also be affected by Covid-19. Some of the signs are associated with mild disease while others are a red flag for a severe version. In Spain, 47% of their Covid-19 patients had a skin rash and in half of these it was itchy. It lasted for about nine days and tended to be associated with a more severe course of the disease. An itchy rash and high temperature is, these days, suggestive of Covid-19, and can occur very early in the disease process.

Covid toe (Chris Curry)

My favourite manifestation of Covid-19 has nothing to do with the lungs, nor the nerves, heart, liver, kidneys, or skin. It is the so-called “Covid toe”. Dermatologists around the world have reported an increasing number of chilblain-like lesions on patients’ toes. Chilblains are painful red or purple lesions that can appear on fingers and toes during winter. With Covid-19, they are appearing even when the weather is hot. This may be due to lots of tiny blood clots that end up in the toe.

When all these symptoms are taken together, it is clear that Covid-19 is a multisystem condition and not just about pneumonia. Sometimes it does not affect the lungs at all. There is still much to discover. In particular, little is known about the longer-term outcome of these various presentations. However, what seems clear is that recovery is not always instant, may be very protracted, and some patients, even if they survive, may never return to normal.

Faced with this knowledge about the present, yet very little of the future, a study has been launched from Leicester to see what happens to patients once they have been discharged from hospital for Covid-19. The aim is to recruit 10,000 patients throughout the UK and to follow them for at least a year, quite possibly longer. This research has been classified as urgent.

And urgent it is. There is much more to know about this unexpected, mystery disease, which is storing up mischief for our future.