Friday 3 April 2020

Not much has changed since the days of the plague (ManuelVelasco)

One of the advantages, maybe disadvantages, of self-isolation is that I spend so much more time reading. As a medic, what better material is there than to read about pandemics of centuries past? Yet the more I read, the more I become frustrated, as medicine seems hardly to have changed. We think we are so advanced, when in reality we are not. Public Health specialists appear to have been saying the same thing for centuries. Society, too, continues to struggle as it did before, and so the turmoil I see around me today may be dramatic and unwelcome, but is not unusual.

The Black Death of 1348 is a perfect example. This was not a coronavirus, as we see today, but the bubonic plague. Swellings, known as buboes, would appear on a victim’s neck, armpits or groin. They could be huge. A variant was the pneumonic plague, which was acquired by breathing the exhaled air of a victim. The disease was caused by a bacterium called Yersinia pestis and was spread by fleas. This was not a coronavirus. Yet the Black Death, which is also called the plague, started out from China, entered Europe through Italy, and Florence in particular. Does that ring a bell? The disease took three years to complete its mayhem. By the time it had finished, as much as 50% of Europe’s population had perished.

There were different reactions to this disaster but, as the Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio wrote:

“…such fear and fanciful notions took possession of the living that almost all of them adopted the same cruel policy, which was entirely to avoid the sick and everything belonging to them. By so doing, each one thought he would secure his own safety.”

Boccaccio wrote The Decameron after the epidemic of 1348, and completed it in 1353. It was the story of ten locals who fled the Black Death in Florence to a villa outside the city. Boccaccio describes the effects of the disease superbly well in his book. In those days it was not called the Black Death but the “pestilence” or pestilentia.

At that time, small communities were formed, where groups of people lived separately from the rest. They ate the best food, drank the finest wine, and allowed no discussion of death and sickness. Others became even more carried away, satisfied every appetite they possessed, went from tavern to tavern, and visited others in their houses. Today we would call them covidiots. Sometimes they would take over unoccupied houses, as so many dwellings had been abandoned when folk fled.

Meanwhile still others decided to go further afield, either abroad, or at least to the countryside around Florence. They were entirely self-centred, cared about nothing but themselves, abandoned their own city, their own houses, and their families. Social order then broke down. Wives would leave husbands, and parents would sometimes refuse to see their children. This was the Black Death in action, as society fell apart.

The lower classes were especially affected, as most could not flee, and were obliged to stay at home, so fell sick and died by the many thousands. Dead bodies piled up, so mass burials were the only option.

Over the subsequent centuries, the plague came and went and was active once again in London during the time of William Shakespeare. An outbreak in 1592-1593 in London killed 10,500 and a subsequent one in 1603 killed 25,000. It is said the plague features in many of Shakespeare’s plays, but the playwright survived and may even have developed immunity to the disease. These were troubled times. It is unknown if Shakespeare fled London to Stratford during these outbreaks, but he may have done. The theatres were certainly closed when the death rate rose too high. In July 1606, in the middle of King Lear and Macbeth, the flag at the Globe Theatre was lowered and the playhouse’s doors were locked. The Globe Theatre still exists, and its doors are once again sealed.

There were intermittent outbreaks of the plague again after this but the outbreak in 1665-1666 was impressive. Then, London lost roughly 15% of its population. Those who could, including most doctors, lawyers and merchants, fled the city. Charles II and his courtiers left in July for Hampton Court and then Oxford. Parliament was adjourned, just as it has been now, but subsequently sat in Oxford. Court cases were also moved from Westminster to Oxford.

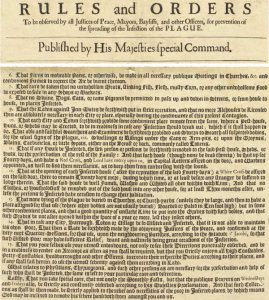

All trade with London and other plague towns was then stopped and the Council of Scotland declared that the border with England would be closed. As there were no fairs or trade with other countries, many people lost their jobs, again just as has happened now. Meanwhile, the King issued orders as to how the people should behave. These were incredibly strict. No stranger was allowed to enter a town unless they had a certificate of health, similar to the immunity passports currently being proposed. There were to be no public gatherings such as funerals, matching current Government advice that funerals should be restricted to the smallest possible number of attendees. No more Alehouses were to be licensed than were absolutely necessary, matching the bar, pub and restaurant closure legislation recently passed. If a house was deemed infected, the sick within were forcibly removed to a pest-house, similar to the enforced quarantine seen at the time of the epidemic’s first wave in Wuhan.

If an infected person was found within a property in the days of King Charles II, the house was then shut for 40 days, a red cross painted above the door and the words “LORD HAVE MERCY UPON US” affixed to it. Capital letters were required. After 40 days, the house was opened, this time a white cross was painted above the door, but no one was allowed in for a further 20 days. Even then, that was only permitted after proper fumigation.

Anyone dying of the plague was not permitted to be buried in normal churchyards, unless they were large, and a specially assigned place was allocated to them. Generally, mass graves were constructed elsewhere. The graves were not allowed to be opened for a full year afterwards, “less they infect others” was the King’s instruction. Today, in some areas, cemeteries are now closed except for funerals and burials. In Iran, specific mass burial sites have been dug, as two large trenches south of Tehran. They are visible from space.

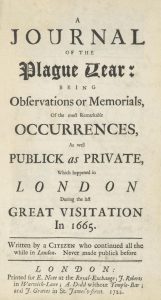

Daniel Defoe, author of Robinson Crusoe, was in London as a child in 1665 throughout the plague epidemic and subsequently wrote what is now regarded as a plague classic. In 1722, his A Journal of the Plague Year was published and is widely cited to this day. He recorded how perilous it was to be a quack and how many of them claimed all manner of therapies to be successful, declaring:

“Infallible preventive pills against the plague”

or,

“Never-failing preservatives against the infection”

or,

“Anti-pestilential pills”

In a subsequent book, Due Preparations for the Plague, Defoe described a family that quarantined itself for nearly six months in London during the peak of the epidemic in 1665. The head of the house stored plenty of provisions, although I doubt that his stockpiling involved loo rolls. When the postman delivered letters, they were smoked with brimstone and gunpowder, sprinkled with vinegar and then read while wearing hair gloves. Once read, the letters were burned. Today, the Royal Mail has taken extensive steps to reduce risks to its staff and customers. Post, it appears, is still seen as a weak link.

This limited history of the plague clearly demonstrates that society realised many hundreds of years ago that other people were the danger when it came to disease transmission and that quarantine was essential. There were different ways of enforcing it but by earlier standards, the enforcement methods we are presently seeing are fairly gentle, even in China’s Wuhan. Throughout history, too, healthcare staff at the frontline of medical care have had a high rate of attrition. Different therapies have been recommended over the centuries, although none was proven successful.

Ashamedly, modern medicine appears not to have advanced greatly in almost seven centuries. Each time an epidemic occurs, society says it will learn its lesson and yet each time little changes. Perhaps this time society will adjust? Somehow, I doubt it.

NHS Nightingale Hospital at the Excel Centre – made in next to no time

Returning to the present, London has now opened its new 4000-bedded Nightingale Hospital at the Excel Centre and the Prime Minister seems to be having a rough ride with Covid-19. He is remaining isolated with mild symptoms.

I am also becoming increasingly concerned by dogs and cats, especially dogs, that plague me whenever I am out for my daily exercise. Owners seem to find any excuse not to use a leash. I now learn that I should be more concerned by cats than dogs. Researchers from China have found that SARS-CoV-2, the cause of Covid-19, transmits in cats via respiratory droplets.

The overall conclusion, at least for the moment, is that cats can pass the virus to cats, but no one has any idea if cats can pass it to humans. Watch that space.