Thursday 16 April 2020

One wave follows another follows another (Tamba Budiarsana from Pexels)

They say that as one door closes, others open and that seems to be what is happening. My tasking at a London teaching hospital, alongside other military veterans, has now been completed and each of us is proud of what we have done.

Over several decades, I have worked with many humanitarian organisations, but I cannot think of any that has been as spirited and supportive as the group with which I have just laboured. When a job has needed doing, there was barely any requirement to ask. There was always a veteran who was prepared to help. It is a team that steps forward when others have stepped back. My time with them has been remarkable, honourable, and a privilege.

We have helped set up an in-house supermarket that is now running smoothly, under the control of the hospital that inspired it. There is a second branch, too, in another hospital nearby, and food packages are winging between the two regularly. I have lost track of the number of staff we have helped, and their families as well, but it is definitely in the tens of thousands. No doubt the organisation will shortly publish its results.

Bigwigs have passed through to lend a hand. By big, I mean that few come bigger. They, too, wish to be seen alongside this growing team of veterans. Yet as this door closes for me, the NHS has once again been in touch, although only with a further list of questions. I sense the NHS is struggling to place its volunteers and is weighed down by administrative requirements. I have several friends who have offered to assist, in different walks of life, and yet even now are waiting for a placement. Sooner or later their enthusiasm will tire, and they will move on to other activities.

The NHS’s query of me is, once again, administrative. It is something called DBS certification, which is the Disclosure and Barring Service. Basically, I have to prove I am not a mass murderer. I sent them the information they needed some weeks ago, and I have now sent them two further forms in the hope I will satisfy their expectations. My guess is their system is swamped. I learned many years ago that with the NHS, anything is possible. What you expect to happen is unlikely. It is what you least expect that will materialise. It is just the way it is. So, the NHS door is open for me, but at present is just ajar.

There is a fair amount to ponder at the moment. It started yesterday evening, when our Foreign Secretary told the country how well it was doing. It appears we are supposed to feel optimistic, as lockdown is achieving what it should. I am not convinced this was the right psychology. My fellow nationals may be in lockdown, but there are still plenty who try to bend the rules.

“I am an exception,” they say. “Lockdown applies to you, quite naturally. But to me? I am somehow different.”

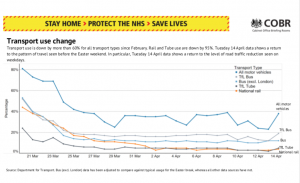

I saw it with the tiny uptick in the graph of the use of motor vehicles. It was Britain trying to escape. During the official briefing, the bigwigs did not mention it, but slightly more people have been trying to travel on the roads, even if public transport is less used. The nation is becoming restless.

Admittedly, the number of patients with confirmed Covid-19 in hospital beds is declining. There is even talk that the country may have overprepared. A few days ago, the new NHS Nightingale Hospital in East London, with a top capacity of 4000 beds, had only 19 of them filled. I do hope the place will not be seen as a white elephant in the days and weeks to come. Permit me to reserve judgement for the moment. I do understand that for crisis planning it is important to prepare for a real drama.

With so much talk about exhausted healthcare staff, and some dying as well, the public is taking matters into its own hands, which may in part explain the figures. No one wishes to go anywhere near a hospital. Over the past fortnight I have talked with many doctors who are working in Accident and Emergency Departments. Each says the same. Their attendance numbers are falling. For example, in March 2018 there were 2,049,785 Accident and Emergency attendances in England. By March 2019 this had risen to 2,167,551, but in March 2020 had fallen to 1,531,100. This is a decline of 29.4% in the last year, a number so low that it has not been seen since data have been collected, which is easily for more than a decade. Emergency admissions to hospital, despite Covid-19, have also declined by a whopping 23.0% when compared with a year ago. The NHS seems to be managing, certainly for the moment.

President Trump has once again stirred up the world by saying that he wishes to open the USA’s states in phases. He is calling it “Opening up America Again” when the place has barely been closed. Guidelines for this reopening have already been published. Meanwhile in UK, we are being told that we have done so very well that our reward is to continue with lockdown. It appears that America is opening up and UK is to remain closed. To add to this clear lack of unity, the London mayor is saying the public should wear masks outdoors, when Government policy says we should not. What is anyone meant to think? There are as many policies for lockdown as there are countries on the planet. Anyway, once America gets back to speed, I look forward to seeing how the rest of the world will remain in lockdown.

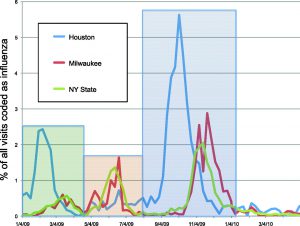

The problem, and this is only just now being discussed, is a second wave. It is most unlikely that Covid-19 will spare us a second wave and it may well make a third. H1N1 did that in 2009, indeed it had three waves, not two. Even more waves are possible for Covid-19. Further waves can behave very differently to the first. For example, the second wave of the 1918 influenza pandemic was more virulent than the first. There was a third wave as well.

The world has experienced multiple influenza pandemics over time. There was the 1918 H1N1 so-called Spanish influenza, the 1957 H2N2 Asian ‘flu, the 1968 H3N2 Hong Kong ‘flu, and the 2009, swine-origin H1N1 influenza A virus. During each of these pandemics there were multiple waves, certainly in the USA. China did not always experience multiple waves. Various reasons for multiple waves have been proposed. School holidays, for example, reduce the chance of a pandemic wave but these are not thought to be the sole cause. Rapid mutations, which do occur, are also thought to increase the chance of a further wave by increasing a virus’ virulence. A third mechanism is a heterogeneous population, where different parts react in different ways, to give the appearance of two waves rather than one. A fourth mechanism is a viral mutation that causes delayed susceptibility of some individuals and the fifth mechanism is waning immunity. Any or all of these mechanisms are possible with a pandemic, which is why subsequent waves for Covid-19 seem to be quite likely.

Already, some countries have experienced the beginnings of a second wave. A few that have relaxed their lockdowns have had to reintroduce them, as numbers have climbed for a second time.

This means that any country’s apparent control of an outbreak may be quite tenuous, so different methods of enforcement exist in different parts of the world. For example, in Singapore, citizens are obliged to share their mobile telephone’s location data with the authorities so their government can be sure official quarantining regulations are being followed.

Citizens get up to all sorts of mischief. Take the report in the South China Morning Post, which said that in Hong Kong a 13-year-old girl was spotted breaking her official quarantine after she had flown in from New York. She went to a Japanese restaurant with her uncle. She was immediately, and publicly, shamed. In Taiwan, a man was fined Tw$1 million (UK£27000) because he skipped quarantine to go clubbing. Both Hong Kong and Taiwan had claimed to have got on top of their Covid-19 outbreak but were not about to relax for a moment. With examples such as this, I suspect that unrestricted travel may be many months away, even more than a year.

Keeping infections out – a quarantine station at Incheon International Airport, South Korea (Lam Yik Fei:The New York Times)

Seasons come into it, too. Work from the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden and the University of Basel in Switzerland has already shown that Covid-19 may well decline as hot weather appears, only to return in the autumn and winter. The researchers took four common coronaviruses called HKU1, NL63, OC43 and 229E, which cause the common cold, and found them to be ten times more common in December to April, than from July to September.

What is clear is that it is important we do not lower our guard. Give citizens an inch and they will take more than a mile.