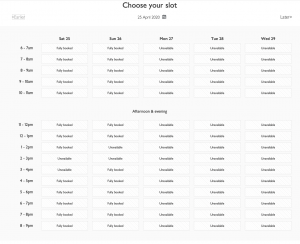

Tuesday 21 April 2020

Emergency Departments have seen a drop in attendances (Pixabay)

Six weeks ago, the NHS’s Chief Executive and Chief Operating Officer wrote to the Heads of every NHS Trust, and asked them to postpone all non-urgent elective operations from 15 April for at least three months. In addition, the hospitals were to discharge all inpatients who were medically fit to leave. The aim was to free up 30,000 of the English NHS’s 100,000 general and acute beds. Emergency and cancer treatments were meant to continue.

The problem is that the UK population now appears terrified of going anywhere near a hospital, so some are hanging on to their diseases while at home. Visits to Emergency Departments have vapourised to their lowest levels for more than a decade and many GP surgeries have all but boarded up their doors. Now, the GPs even have themselves organised for the remote verification of expected death, certifying death by video. What has happened to our world? So much of life is now conducted from a distance, as if by remote control, as the nation has been told to stay at home and, quite simply, to get on with it.

The situation this morning – 21 April 2020 (courtesy Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University)

However, the possible fall-out from utter focus on Covid-19 and the reduction in elective treatments, which has been translated by so many into a complete cancellation, may turn out to be more harmful than Covid-19 itself. It is critical to realise when surgery is called elective, it should not imply it is optional. It simply means it is non-urgent. A good friend and colleague of mine in Chicago (USA), who personally handled many of the casualties from 9/11, describes it well in an article he has recently written:

“Federal and state governments have recommended a complete stoppage of all “non-urgent” procedures. Women cannot get annual mammograms. People with heart disease cannot get routine blood tests. Cancer screenings are becoming an afterthought. As a nation, we are in grave danger of pushing aside every aspect of medical care that is not related to COVID-19, and if we do not act quickly to balance our efforts, the conditions we are ignoring may incur a human cost that could far overshadow that of the virus.”

The UK has now been advised that restrictions will last for longer than many first anticipated and may even be in place until next year. So be it. By then I will easily be able to recite Netflix’s content by heart. The one film I do not wish to recite is Contagion, starring my hero, Matt Damon. It was released in 2011 but, should you see it, you will be astonished how accurate it is. I do not believe the film is for the fainthearted, which is perhaps why, in its day, it made a whopping US$135.5 million at the box office.

Contagion apart, well before the Covid Crisis researchers looked into the outcomes of delaying or cancelling operations. Certainly, with a government-driven health system like the NHS, cancellations had almost become a way of life for its healthcare practitioners. Work from Sweden suggested that delays or cancellations of elective surgery could be followed by inferior clinical results. Patients could be harmed by these delays and that was not just a Swedish experience.

There is plenty of work in the scientific literature to say that delaying operations or other treatments can be to the detriment of a patient, although the outcomes depend very much on the condition being treated. For some conditions a moderate delay is not so bad, for others it can be catastrophic. In addition, cancellations can have important emotional and economic impacts on families. Investigations may have to be repeated and the number of journeys between home and hospital increased. There are also significant rises in hospital costs and utilisation.

The bottom line is that it may seem simple to postpone or cancel elective surgery across the board, but it can only be done for a certain period of time. Basically, the shorter the better. When the bigwigs stand before the nation every evening to brief us all on the crisis, I have yet to hear any of them mention elective surgery. Despite the hazards of Covid-19, the nation ignores elective practice at its peril. The delays will catch up with us in the end.

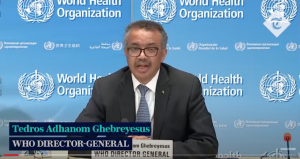

I didn’t say it, he did. The worst is yet to come.

Today the WHO carried a message of doom, just when I was hoping to be optimistic. “Trust us, the worst is yet ahead of us,” said Tedros Ghebreyesus, the Director General of the WHO. If you seek a sobering moment, have a look at his video.

Basically, we are being told that the easing of restrictions is not the end of the epidemic in any country. The problem is that lockdowns can take the heat off, but they cannot end the disease. The WHO stance has been reinforced by others, notably Robert Redfield, the Director of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), who has warned that a second wave of the virus is expected to hit the USA next winter and could strike harder than the first. The worry is that there will be ‘flu and Covid-19 at the same time. Heaven forbid that I might relax for a moment.

Lockdown is definitely taking its toll if I look around the world. In UK, we are just one of many. I gave a lecture on Zoom to an audience yesterday evening and although it was good to see so many faces – there were easily over 150 – most looked pale and sallow. Even the viewers with gardens, I have no such thing in London, have been stuck indoors for longer than is healthy. As my study is in desperate need of a tidy, and I have no wish to highlight my disorganisation to the wider community, I have given up having a normal backdrop to my face when I am on-screen. I go for something happier. Waving palm trees are my favourite, on what I think is a West Indian island. When I wish to appear academic, my background changes to a musty library, filled with out-of-print books.

Supermarket deliveries are also proving a challenge as they seem near-impossible to order. Everyone realises their importance. On another conference today, surprisingly jolly considering it was about how to handle bereavement, one of the supermarkets went “Ping!” on my mobile, and before I knew it there was a delivery at my front door. The moment I told the meeting organiser, who was somewhere on England’s south coast, that I had to collect a delivery, her reaction was instant.

“You must collect it,” she said, without a moment’s hesitation and looking delighted for my good fortune. “Go right away. Deliveries are as rare as hen’s teeth.” I would guess this I something with which the entire UK population would agree.

The other attendees each nodded their understanding. Videoconferences sadly do not permit a High Five, but had we been together in a room somewhere, and ignored social distancing, I am sure that is what my colleagues would have done. I disappeared off instantly, collected the delivery at my front door, and returned to the meeting with a skip, although a week’s supply of fish fingers was already starting to defrost on my kitchen floor. I would put them in the freezer later.

Yet for sure, if you wish to make someone jealous during this crisis, just say a supermarket delivery has arrived. That will earn you far more prestige than any level of salary, or some posh holiday which has cost a fortune.

Deliveries are as rare as hen’s teeth during lockdown, without great signs of the situation changing.