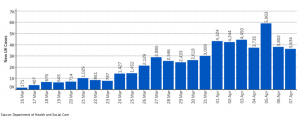

Tuesday 7 April 2020

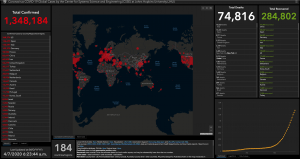

Hospital staff are exhausted (Andrea Piacquadio)

It has started. At least a new phase for me in this crisis has begun. I am now based in a large London teaching hospital, not far from the city’s centre, and despite the global chaos, it is a blue-skied sunny day. Our Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, is also in a large teaching hospital, but that is where the similarity ends. Not only is he head honcho, but he is also a patient, dependent on oxygen in his hospital’s Intensive Care Unit.

The word on the street is that he will be fine, but I am rapidly learning that with this new disease you simply cannot trust the virus. Barely a day passes without something new being discovered. A cure? No chance. Vaccination? One day, perhaps. Cough, fever, headache, gut-rot, even loss of smell? For sure, the coronavirus can present in a myriad of ways. In brief, if you feel off-colour these days, you must think of Covid-19. Its presentation is not always a classic dry cough and fever.

I form part of a team of military veterans that has responded to the call. I have been to many, many disasters right around the world, and over far too many decades, but always they have been someone else’s. This is the first time in my existence I have responded to my own.

The Team to which I belong has instantly bonded, I am sure because most members are ex-Services. Banter is flowing like a running tap between strangers who have only just met. Service life does that. The ability to be outrageously jolly one moment but deadly serious the next. You would get a slower response from a light switch.

The organisation’s pre-deployment administration makes other organisations pale. I received documentation, was security checked, and completed forms and disclaimers in less than 24 hours. I have a Team Leader, I am told ahead of time where I am meant to go and who will be joining me, I know where I will be sleeping, and briefings are already underway.

Our first, on-site briefing was given by a hospital employee who in normal times helps with the investigation of patients. Everyone in the hospital has changed direction. Surgeons have become physicians, porters have become security personnel, and then look at me. One moment I am in the Middle East sorting out the war wounded, because that is what I do, and now I am in my own capital helping fight a virus that few are able to see.

The briefing room was in an older, more historic portion of the hospital. It had high ceilings, panelled walls, chandeliers, and oil paintings of serious people looking down from above me. The chairs were spaced to allow for two-metre social distancing. When I paced out the gap between them, I reckoned it was almost three. One look at the lay-out and I could see the place was taking this virus seriously.

Do you really want to find this after a long day treating Covid-19?

Our tasking was clear, although was yet to be implemented. The hospital staff were exhausted, and the NHS was rightly focussed on its workers. It needed to keep them supported and on side. Many patients were dying, and it was not all old wrinklies. There were youngsters who were desperately sick as well. In healthcare it is possible to take that for a period, but day in, day out, night in, night out, the physical and emotional load is extreme. Hospitals are designed to bring patients in and send them home better. That is how healthcare staff think. These days it is different. With Covid-19 there are too many patients who are not making it home. For anyone at the frontline of healthcare that is an enormous pressure. Post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD, is a risk and something with which the military is more than familiar.

Thanks to a nation obsessed by loo rolls and stockpiling, by the time the hospital staff went shopping, should they have had the time at all, London’s supermarkets had been stripped bare. Healthcare workers keep long, strange hours. They will frequently start before society awakens and finish too late to make it to the shops. The hospital had a brainwave. Why not make its own supermarket and reserve it just for staff? Emergencies being just that, decisions do not take long, and in no time a supermarket was created in an upmarket marquee at the tail-end of the hospital. I am here, we are here, to offer logistics and muscle.

Muscle? As the briefing continued, and in the hope I remained unnoticed, I slowly grabbed my right bicep between left forefinger and thumb and gave a firm squeeze. Then I shook my head infinitesimally. Pathetic, I thought. My bicep was too spindly, and I felt ashamed. I should have kept going with those 100 push-ups that I once did religiously at the end of every day. Somehow those disappeared and it was now too late to rectify. I could not click my fingers and become an overnight Tarzan. As the briefing carried on, I wondered if I had the strength to do the heavy lifting the task required.

At the briefing I heard that donations had been pouring in, sometimes unannounced. The entire country outside the hospital walls was in support. Any donation was welcome, whatever it contained and whenever it arrived, although sometimes the timing could be better. When three articulated lorries filled with biscuits, and a single truck laden with intensive-care oxygen, arrived simultaneously and vied for the two loading bays on the ground floor of the hospital, serious control was required. Happily, the oxygen made it through as a priority. It is with such decisions that the military can be effective.

Briefing over, I was given time to find my accommodation, which the hospital had placed in a hotel across the road. It was only a short walk. The place was massive, I had to strain my neck to see its top, and the hospital had taken many of its rooms. I realised, with so many hospital staff staying there, a Covid-19 risk existed. The hotel already knew that and had installed so many hand gel dispensers that I was sure it would be possible to conduct a full gel body wash if I was up to the challenge. I am unsure if that has ever been done.

When I checked in, I was pleased to see the receptionist kept her distance by far more than two metres, and my room key had been prepared ahead of time as I retrieved it from a table a long way from the main desk. The hotel had manifestly thought things through.

My room was on the 13th floor, which made me think for a brief moment. There is something about a crisis that makes me suspicious and I start believing in things that would normally make me giggle. Thirteen? Did I really want to go there? In the end I shrugged my shoulders, smiled at the receptionist, and headed for the lift. I let two pass without entering. With disease around, there was no way I would be sharing a closed container with anyone. I waited until I had a lift to myself.

I threw my duffel bag on the bed and then headed back to the hospital for the second part of my briefing. This time it was Occupational Health that had issued me a form for completion. I was asked to own up to any illnesses I might be hiding. I denied everything. It was simpler that way. I had nothing of consequence anyway, but did they really want to know that I had a tickle in my throat last November? Or, how about the London cocktail party six weeks earlier, where I had met Chinese diplomats and spent a good hour talking about Covid-19? Four days later I had started coughing, I could not understand why, and a few days after that it had settled. I never felt ill, even once. Forget it, I thought, so I stated I was fully healthy, and the form was taken away.

Briefing complete, I walked outside the hospital to take some fresh air. And yes, thanks to reduced traffic, the London air is now properly breathable, and the Thames water is verging on clear. There must be some advantage to this wretched virus. I strolled around the building, diving into doorways and behind potted plants to keep my social distance, like Inspector Clouseau from a Pink Panther movie, creeping down a passageway while trying not to be seen.

It was as I darted left and right, while wondering if I should, that I heard the wailing. On the concrete path that led to the hospital’s main entrance prostrated a woman, facing towards the hospital. There was some strange sound coming from her that I could not identify. Perhaps, I thought, it could be a prayer. The next day was, after all, the Jewish Passover.

A large, religious tome was open on the ground in front of her, although I could not see if this was a Bible or some other holy book. Meanwhile, a group of short-sleeved policeman, three men and one woman, stood around her, trying to move her on but failing. The police were attempting to work a way out of their dilemma as the supplicant was doing no harm. They were not about to pick her up if she had Covid-19.

I heard them ask passers-by, “Does anyone speak Spanish?” When they asked me, I shook my head and shrugged.

“Good luck,” I whispered, as I walked past.

The situation this morning – 7 April 2020 (courtesy Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University)

The hospital-inspired supermarket had already opened and had been going for a full week. It was proving popular and successful but was also arduous to run. It had seen 500 people on its first day and was why former Servicemen had been summoned. The local team were normally in clinical practice but had been reallocated to make a supermarket possible. Each member was brilliant and invaluable, and each sported a bright yellow tee-shirt that was impossible to ignore. When lost, I asked someone in yellow. If confused, I asked someone in yellow. If I needed to know anything at all, yellow was what I would seek. The colour was so bright, I checked in my pockets for sunglasses.

Dammit, I had forgotten to bring them.