Friday 17 April 2020

Slightly the secret agent, I sneaked out for a Covid test (cyano66)

I did not expect to behave like a secret agent while in the middle of a lockdown, yet somehow it appears that I did. It started when I decided to see if I had previously suffered from Covid-19.

Two months ago, I was working alongside some Chinese diplomats and as part of our discussions about this and that, I mentioned the disease.

“You’re doing wonderfully with your quarantine,” I said, unaware that two months later I would be experiencing the same. I was also unsuspecting that China would soon be accused of a cover-up, or even accidental virus leakage.

I sounded like a bullfrog

The Chinese nodded, smiled inscrutably, and our conversation then moved on to other things.

A few days later I started coughing, thought nothing of it and then improved. The cough lasted all of three days and made me sound, and probably look, like a bullfrog. Life moved on until the last few weeks, when I spent a lot of time in close proximity to patients with Covid-19. I saw colleagues fall ill and have to self-isolate, I saw passers-by cough and sneeze unprotected, and found myself in situations where social distancing was impossible. Thankfully these were few.

Because of my work and location, I was a dead ringer for catching the bug. Yet somehow, right now, I appear to have escaped. That does not mean that tomorrow life will be the same. However, it has made me think. Could I be immune? Why have I been spared? It was time to have a test to establish if I had any antibodies, and thereby possible immunity.

I telephoned my doctor – everything seems to be by telephone these days – put the problem to him, and he said someone would ring me back. Five minutes’ later I was talking to an authoritative voice, another doctor working remotely, about my chances of having Covid-19 and why I wanted testing.

“That’s OK,” said the distant medic, after listening to my story, “but you must realise the limitations.”

I nodded, a futile gesture on a telephone, and was told someone else would ring me at any moment.

The next call was almost instant. No prizes for guessing. It was the Finance Department of the practice, seeking my credit card details to pay a small fortune. I passed them across without complaining as a test was what I sought, although the price made me dip into my life savings. An appointment arrived by a further call, and a confirmatory email then followed. I was to report to an address near to where I lived but to be quick about it and not hang around outside.

“Should I wear a red carnation in my buttonhole?” I asked, realising I was being over-flippant.

“Wear what you like, sir,” came the reply. “Just remember we are in lockdown and we do not want too many people wandering the streets.”

A short while later, I set out, heading towards the address I had been issued. I scurried this way and that, looking over my shoulder, around every corner, hoping not to be noticed for fear I was doing the wrong thing. I felt like the imperfect spy. Yet soon I arrived at a narrow, four-storey townhouse, and outside it on the pavement stood a line of five people. I was number six. Two others were sitting in a nearby car, parked on a London double yellow line.

“Are you…umm?” I asked of an unmasked man in his mid-thirties who was standing at the head of the queue.

“Yes,” he nodded secretively. “Are you…umm?”

I nodded, too. The man turned to an unsocially distanced woman behind him and said, “He’s here for…umm, as well.”

Her masked face nodded. It seemed that no one wished to admit why they were standing in line.

Moments later the front door opened, and a masked face popped out. “Who’s next?” asked a female voice.

“10:30 appointment?” I queried.

She nodded and I was in. Somehow, I had reached the head of the queue without actually queuing. Once inside the front door it was clear the place was heaving with mankind. I must have seen at least 20 people, some waiting, some talking, but all, to be fair, socially distanced.

I was shown to the third floor, where I was the only arrival, and ushered into a small room and told to take a seat.

This lot do not recommend the test I sought

“I will ‘ave to preek your feenger,” said the French lady from behind a visor, mask, gloves and full-length gown.

“By all means,” I replied, offering my right forefinger. Within moments the woman had made a painless hole in my fingertip, I do not understand why it did not hurt, and squeezed out a large drop of blood. She then placed the red stuff into a small well on a tiny piece of plastic. Then all I had to do was wait ten minutes and the plastic told me the result.

This was the so-called antibody test, which had recently arrived in London and I had chosen to have one privately. The Government, the WHO, and organisations in between, have been straining every sinew to say that the test’s accuracy is far from assured. So be it. I understand that. Yet I see nothing wrong about knowing more about oneself, as long as you realise the inaccuracies.

What was clear was that there were many, many others who had joined me. The London townhouse was burgeoning with patients during my short ten-minute visit, and its appointment book was filled all day. And tomorrow, and the next day, and the days after that. The British public hears what is being said by the high-and-mighty but does not necessarily believe all it is told.

The principle of the antibody test is quite simple. A virus is an antigen, and when it attacks a human, antibodies are produced as a result. The antibodies are meant to neutralise the antigen. Once neutralised the human becomes better, or at least their condition should improve. Some antibodies disappear quickly, some take longer, but while they persist the human has resistance to a further viral attack. This is called immunity. It is also what vaccines do. A vaccine is a virus lookalike, of lesser potency than the real thing, which can excite the formation of antibodies, so the human becomes resistant.

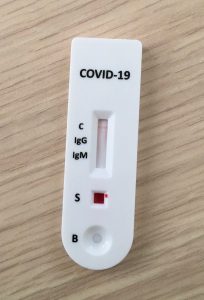

The test I had undergone, thanks to a French lady behind a visor, is a variety of what is known as a rapid IgM-IgG combined antibody test for Covid-19. IgM stands for immunoglobulin M and is the first line of defence during a viral infection. IgG stands for immunoglobulin G and imparts a longer-term immunity against a virus. In the days of SARS, IgM could be detected in a patient’s blood 3 to 6 days after infection while IgG could be found after 8 days.

Sadly, the test is not a hundred percent reliable. In fact, the WHO says this:

“WHO does not recommend the use of antibody-detecting rapid diagnostic tests for patient care but encourages the continuation of work to establish their usefulness in disease surveillance and epidemiologic research.”

They tell me this means I am Covid-negative

Some research has been done on these rapid antibody tests. For example, a Chinese group looked at 179 patients, split into 90 with proven Covid-19 and 89 without. They based their proof on whether the patient had Covid-19 on a PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test. For the patients who were PCR positive, and thus had Covid-19, 77 of them had a positive rapid antibody test. That gives the test what is called a sensitivity of 77/90, or 85.6%.

For the 89 patients with a negative PCR, who did not have Covid-19, 8 of them had a positive rapid antibody test. This gives the test what is called a specificity of (100 – 8/89), or 91%. The authors concluded that the test was easy to use, did not require a skilled technician, and would be useful for mass testing. Other authors have said something similar. However, at the moment it cannot take the place of a PCR antigen test for accuracy.

Part of the problem with the antibody tests is that the antibodies are produced days and weeks after the initial infection, not necessarily at the time, and the strength of the antibody response can depend on a number of features, including age, disease severity, and other medications. The tests may also cross-react with other coronaviruses and give a false-positive result. A false-positive, in doctor-speak, is when the test says that a patient has the disease when in actual fact they have not.

The only consolation for an old codger such as me, if work from the USA in the Journal of Medical Virology is to be believed, is that older folk are said to reach higher levels of antibodies than the younger ones. We are bumped off more easily, that is for sure, but if we get through and out the other side, maybe us old’uns might last?

I hope not to find out. So far, if my rapid test is to be believed, I have managed to avoid infection. No thanks to passing joggers who keep showering me with sweat.