Saturday 18 April 2020

There will be time later for awkward questions (Redrecords from Pexels)

Sometimes I am ashamed to be a writer, especially when I hear the questions certain colleagues ask. I realise a journalist’s job is to probe, but sometimes you have to be careful. Right now, there are plenty of queries, challenges and arguments in everyone’s mind, but is today really the correct time to suggest that, somehow, our leaders have got it wrong?

In lockdown, when there are already significant stresses to us all, the last thing I want to hear is that my country’s leadership is askew.

“He should have done this,” one reporter states.

“She should have done that,” another observes.

“Why did they not do something earlier?” a popular radio channel proclaims.

And still they continue.

Slowly I see my society unravelling and I can now appreciate how pandemics through time have changed the course of history. I see that through my own eyes in 2020. Societies seem to believe that a government can be prepared for something that is unpredictable. If things go wrong, then had the government handled things differently, the outcome would have been better. Dream on. It is not the way life works.

Many famous names have predicted our current drama. Bill Gates, for example, during a TED talk in March 2015, focussed on the global response to a pandemic. He was talking barely 12 months after an outbreak of Ebola, where a combination of selfless work by healthcare staff and a dollop of good luck, prevented the Ebola from becoming truly global. Gates’ lecture has had nearly 31.5 million views and has the most apt of titles, “The next outbreak? We’re not ready.”

Stephen Hawking predicted this

A year later, Stephen Hawking, the British physicist and cosmologist, declared that scientific progress was almost certain to bring disaster to planet Earth within a thousand years. He subsequently reduced that to one hundred. The threats he outlined were nuclear war, catastrophic global warming and genetically engineered viruses. He believed that mankind would have to escape from this fragile planet in order to survive. If Covid-19 does nothing else, it is highlighting the delicate nature of Mother Earth.

For centuries, pandemics have caused significant social and political upheaval. They represent a direct threat to the power of the state, erode prosperity and destabilise both a country’s internal politics and its relationships with other states. Andrew Price-Smith shows this eloquently in his book, “Contagion and Chaos.” Look now at the beginnings of unrest in the United Kingdom, or Europe introducing frontier checks. Civil disorder is slowly beginning to bubble.

Far back in time, great plagues have certainly changed the course of history. The Plague of Athens (430-426 BC) broke out at the start of Athens’ 27-year conflict with Sparta. The disease, which still remains unidentified, originated in Ethiopia and killed one-third of Athenians in three years. Ultimately, this plague ended Athenian political, cultural and economic dominance.

Smallpox was not a good thing to have

The Plague of Galen (165-180 AD), which was thought to be smallpox, not only killed the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, but over more than 100 years killed five million Romans. This likely led to military, economic, political, and social decline with the eventual collapse of the Western Empire. The disease came from the East, probably Persia, and spread rapidly throughout the Roman Empire. Galen, after whom the plague was named, was the foremost medical authority of the time.

There then followed the Plague of Justinian (541-543 AD), likely the bubonic plague caused by a bacterium called Yersinia pestis, and which again probably started in Ethiopia. The Emperor Justinian, who was the Eastern Roman Emperor from 527 to 565 AD, acquired the disease but survived. Sadly, the empire did not. Byzantium found itself with insufficient soldiers to defend its borders and the empire was overrun. By the time the plague had disappeared, 30 million people had perished. Justinian, unsurprisingly, is sometimes known as the Last Roman.

The subsequent Black Death was the most fatal pandemic in human history, peaking in Europe from 1347-1351, and was again caused by Yersinia pestis. It killed one-third of all Europeans and is said to have ended feudalism by approximately the 15th century, as it reduced the nobility’s hold over the lower classes.

Thanks, it is said, to Christopher Columbus, smallpox was introduced to the Americas by the early 1500s. The Americans had no immunity to European diseases, so the indigenous American population was decimated in no time. This meant that relatively small numbers of Europeans could assert their dominance.

Move forward further to the 19th century and a series of pandemics caused by Asiatic cholera. The first pandemic wave seemed manageable, but subsequent ones were a problem. The Cholera Riots occurred when the second cholera pandemic reached Russia in 1830-31. The urban population, as well as peasants and soldiers, took to the streets thanks to the anti-cholera measures, such as quarantine and migratory restrictions, introduced by the government.

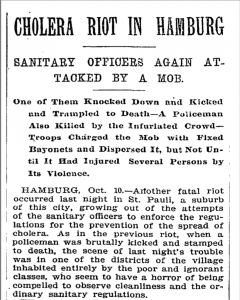

Newspaper cutting from 1893 during the Cholera Riots

Cholera had arrived in Great Britain by 1831, although the main epidemic occurred in 1832. There were riots in cities throughout the country at that time, frequently directed against the authorities, and doctors. England’s north-west was a particular trouble spot, Liverpool in particular. Cholera was also the cause of later riots in Germany (1893) and more recently in Zimbabwe (2008), when doctors, nurses and union members protestedas they sought better pay. Still in Africa, but during the Ebola epidemic in 2014, steps taken by the authorities to mitigate the disease, for example the imposition of quarantine and curfews by the security forces, led directly to riots and violent clashes.

What seems clear is that looking through history, with widespread disease comes social trouble. So far, with Covid-19, we have modelled the progression of the disease, but not yet its social consequences. Experts are already warning that society can expect more protests, looting, and even queues for food. When Michigan extended its stay-at-home order only a few days ago, hundreds of demonstrators protested at the Capitol building in the city of Lansing. The United Nations Security Council has been warned of violent conflict, the head of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies has spoken of possible social unrest in Europe’s biggest cities, while high unemployment and stagnant economic activity are a tinderbox as they are the two most important determinants of social unrest. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has also spoken of waves of social discord in some countries if government measures to mitigate the Covid-19 pandemic are seen as insufficient or unfairly favouring the wealthy.

No wonder the UK military has put 20,000 personnel on standby and the new Covid Support Force has been created. Operation Rescript is now underway. Its objective? To maintain public order – note this primary task – and assist public services and civilian authorities in tackling the coronavirus outbreak.

Social unrest is a clear worry and the media should instantly stop challenging our leaders. There will be time for that in the future.