Wednesday 3 June 2020

Leave the windows open (Blair_witch)

I am one of those annoying people who has to sleep with a window open, whatever the temperature outside. I have sometimes come to blows in mountain refuges, especially with the French, when fellow sleepers in a bunkroom have insisted on keeping the windows closed. The French, it appears, adore sleeping in a fug.

Yet now, in the middle of a Covid-19 pandemic, I sense opinion is going my way. There is plentiful evidence amassing that there is a much higher chance of becoming infected indoors rather than outside. If there is a next time for me in a mountain refuge, I will make a beeline for France and see if the locals have now changed their ways and are happy to sleep with open windows.

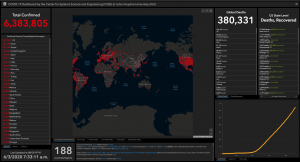

The situation this morning – 3 June 2020 (courtesy Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University)

Roughly two months ago some research came out of China and Hong Kong, which looked at 318 outbreaks that involved three or more cases. The aim was to establish the environment in which the disease had been acquired. The results were fascinating. Home outbreaks were the commonest with 79.9% of cases starting there. Transport was second, at 34%. I could not work out how these numbers totalled more than 100%, until I learned that many outbreaks involved more than one category. But tellingly, of the 318 outbreaks, the researchers found only one that began in an outdoor environment. Even then, that was only two cases.

It is thus no wonder that our government is saying, as it slowly reduces lockdown regulations, that it wants the British public to stay outdoors. It is said that the chances of catching Covid-19 are 19 times higher indoors than they are outside a building.

However happy you may feel indoors, it comes with problems. For example, the ventilation systems of buildings have become a source of worry, especially in lands that rely on air conditioning. A paper from Oman and UK flagged up its concerns about this. The researchers concluded that the harsh climatic conditions of Middle Eastern countries can make it impossible for the

Best give incense a miss

buildings to use natural ventilation systems. Furthermore, the indoor air temperature of most buildings is very low because of the overuse of air conditioning. This low temperature can potentially increase viral spread. Even worse is the burning of incense, which is very common in the Middle East. The small particles produced by this activity can facilitate the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory droplets. On this basis, it perhaps makes sense to give incense a miss for the moment. There is already plenty of evidence to suggest that air pollutants give a higher chance of doing badly should Covid-19 be nearby.

Appropriate building engineering controls are clearly important. These should include effective ventilation, enhanced by particle filtration and air disinfection, as well as avoiding air recirculation and overcrowding. Often, such measures can be easily implemented and without much cost, but only if they are recognised as being important.

Air recirculation may appear to be energy-efficient, but air should not be recirculated. If possible, air conditioning units should operate on 100% outdoor air. If disabling recirculation is not feasible, then maximising the outdoor air level, as well as using filtering or ultraviolet irradiation of recirculated air, can help. In areas of known air stagnation, other air circulation systems can also be used, but only if they bring in outdoor air. In addition, smaller rooms can benefit from portable consumer air-cleaning devices, as long as they have suitable rates of clean air delivery (26 to 980 m3/hr) and their filters are changed when needed.

Hospitals are also indoor establishments and can be dangerous places to be, which perhaps explains the population’s reluctance to go anywhere near them at the moment. In 2007, a group from Hong Kong published an explanation as to why, during an earlier SARS outbreak, the disease had occurred on some hospital wards but not on others. To do this, they looked at 86 wards in 21 hospitals in Guangzhou and 38 wards in 5 hospitals in Hong Kong. Six risk factors pointed towards an increased infection rate. These were the availability of washing and changing facilities for staff, and whether resuscitation was ever performed on the ward. If you wish to see a truly aerosol-generating process, just look at a resuscitation taking place. There are droplets everywhere. Other factors included whether staff members worked while experiencing symptoms, and whether the first patient admitted to the ward with SARS required oxygen therapy. However, very important was the distance between the patients’ beds. One metre or less and there was trouble. Even Florence Nightingale understood the importance of space and ventilation. She increased ventilation, added windows, improved space and saved a huge number of soldiers’ lives during World War I as a consequence.

Air conditioning can be a risk of viral spread (serezniy)

Airborne transmission of disease has long been a problem that has challenged medicine, as it has been found with influenza, measles, tuberculosis, SARS and MERS, too. Washing hands is a fairly simple manoeuvre for people to understand, but airborne transmission is a much harder thing to avoid. Research in military trainees showed that acute respiratory disease was significantly higher when soldiers were in barracks. The same was found in prisons, where respiratory disease was the greatest among inmates in cells with the highest carbon dioxide concentrations, and the lowest rate of outside air delivery. Ventilation has also been linked to sick leave. The worse the ventilation, the greater the sick leave.

So outdoors it is and should remain so. It is just as well this pandemic has occurred while the weather has been favourable. As both the BBC and subsequent media outlets have reported, Dr Chris Smith, clinical lecturer in virology at the University of Cambridge stated, “the chances of Covid-19 transmission outside are vanishingly small because the amount of dilution from fresh air is so high.”

Space and fresh air have long been known to benefit recovery from infection, although the science to support it has sometimes been imprecise. The finding is not just confined to Covid-19. For example, in the years before antibiotics became available, open-air therapy was the standard treatment for tuberculosis and other infectious diseases. In my early years as a surgeon, I worked in several old tuberculosis hospitals, which had been converted into orthopaedic surgery units. Yet the buildings still had their wide-open verandas where, in the era of tuberculosis, patients would be left all day in their beds in order to aid recovery. At the time, outdoor air was considered capable of actually killing the bug, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, that caused the disease. One researcher of the time stated:

Fresh air, space and sunlight keep viruses at bay (Marcin Wiklik)

… abundant fresh air, together with sunshine, acts antiseptically upon both the bodies and the clothing of patients, destroying all organic impurities which may emanate from either, and so purifying the air that enters the respiratory organs.”

In the 1960s, scientists undertaking biodefence research established that outdoor air was far more lethal to bugs than indoor air, both by day and night. They even gave it a name, the Open Air Factor (OAF), which described the protective properties of fresh air. The moment air was enclosed, so this property would vanish but could be re-established if ventilation rates indoors were sufficiently high. The OAF can be fully preserved in a room where there are 30-36 air changes hourly.

Basically, if you want to remain free of Covid-19, get outdoors and stay there, leave windows open when you can, and keep a good distance from others. Only then will you improve your odds.