Saturday 13 June 2020

You do not want to be in a choir when Covid-19 is about

I find it odd that the nation is largely talking as if the virus has gone, and the thing has vanished forever. I only have to look at the global figures to know that any respite is transient. Global cases are increasing by up to 150,000 daily, and those are the ones we know about. There will be many others that remain hidden. All I known about this pandemic is that nobody truly knows anything. Nations are having to respond to changes at a moment’s notice. Because a nation seems good today does not mean it will be good tomorrow. While all this goes on, society is wishing life better.

The situation this morning – 13 June 2020 (courtesy Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University)

Look at the south-west of England. For the moment, in London we are sitting happily. Two months ago, when the capital was badly affected, the south-west was fine, and no one would touch Londoners with a barge pole. Yet thanks to the easing of lockdown restrictions, and the dash of many thousands of covidiots to the seaside in recent weeks, the boffins have projected that the south-west will soon have the highest viral reproduction rate in the land. Once largely untouched, the region is now said to have an R rate of 0.8-1.1, which is not a happy value. Anything above 1.0 means that the bug is on the rise.

The government, which wishes to portray a positive image, has said that this figure for the south-west is an, “outlier of the central estimate.” Really? Somehow, I do not think so. It is an indication of the future.

Despite the pandemic being in the centre of public life for the past six months, much of the nation still appears not to understand how it is transmitted. Day after day, weekend after weekend, there are those who choose to play chicken with a bug they cannot see. They believe that because they feel fine, they are no danger to others. They believe that because they may not be in an at-risk group, it does not matter if they become infected. Oh dear. What does it take to get through to them?

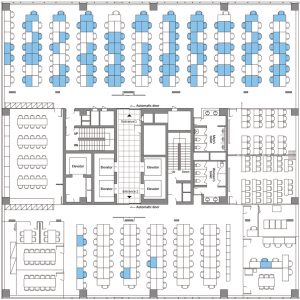

Floor plan of a South Korean call centre. The cases of Covid-19 are coloured blue

Indoors is an especial risk. Look at South Korea in early March, when public health officials learned of a Covid-19-positive patient who was working in a call centre in Seoul. The problem? The office was on the eleventh floor of a 19-storey tower block, in which more than 1000 people lived or worked. In fact, the outbreak that followed was very concentrated. It turned out that there were 97 people in the building who tested positive, of whom 94 worked in the call centre on the eleventh floor. The call centre was split in half across the storey. On one side the disease was transmitted to two-thirds of the employees, on the other it barely featured. This was despite considerable interaction between workers, not only from the call centre, when they met on different floors and in the elevators and lobby. South Koreans are a sociable nation. They certainly beat even the USA when it comes to the use of social media. The finding suggested that fomites, that is touch points such as door handles and elevator buttons, were not a big issue. It was shared airspace that was likely to have been the problem.

To show this point still further, in January, a Chinese family of five ate lunch in a crowded restaurant in Guangzhou. They had gone there from Wuhan, the day before. The restaurant was on the third floor of a five-storey building. It was busy with 80 guests and had no windows. The family sat at a table along the back wall of the restaurant. There was a table each side of them, at which local families sat, while an air conditioner cooled the three tables. That same day one member of the Wuhan family felt ill, went to hospital and was diagnosed with Covid-19. Within a fortnight there had been ten guests from that restaurant who had developed the disease. Each had been in the direct path of the air conditioner. The one person had managed to infect nine others. That person was said to be asymptomatic at the offending lunch, but we will never know if that was truly the case. There were many other guests and servers, none of whom developed the disease.

It is not all China and South Korea. Many countries have similar stories. In March, 61 singers attended a choir practice in Skagit County, Washington State, USA. The practice lasted only two-and-a-half hours. Five days later, several choir members had developed a fever. Eventually, 53 of the 61 singers fell ill, three were hospitalised and two died. These infections, some tragic, were traced to a single choir member who became ill three days before the fateful practice and who was considered to be the index patient. Why this individual attended in the first place may be clear to them but not to me. The index patient did not do their fellow singers a service. Two-and-a-half hours of singing with one index patient bellowing, I am sure in perfect tune, and there were 53 infected. Two never made it home from hospital. That does not seem a good average. No doubt each member of that choir felt fine at the start and had decided that, whatever it was, disease would not affect them. When it comes to a contagious virus, life is not like that. Be warned, fans of mass gatherings, the virus is coming to get you, however immortal you may feel. Keep looking over your shoulder and give the beastie the widest berth.

Jeanne Freeman, Scottish Health Secretary whose estimate of 125 Covid-19 infections in Scottish hospitals was woefully too low (The Telegraph)

Not only is it mass gatherings, call centres and air conditioning blowing bugs across a restaurant. I was also interested to hear that the bigwigs have begun to speak more freely about hospitals themselves being dangerous places. The Health Services Journal reported that the spread of Covid-19 in hospitals is of national concern. You bet. For those of us who are medics, and plenty of others as well, we have known for a very long time that hospitals are major transmitters of disease. NHS England’s patient safety director, Dr Aidan Fowler, stated that he was, “concerned about the rates of nosocomial spread within our hospitals.” Nosocomial is doctor-speak for a hospital-acquired disease. There are plenty of other examples, not just Covid-19. Thrush, MRSA, tuberculosis, urinary tract infections, Legionnaires’ disease. The list is lengthy. Hospitals are not always clean places.

To put the problem in a numerical perspective, it now seems that at least one in five hospitalised patients with Covid-19 caught the bug in hospital. These figures are likely to be an underestimate. All hospitals have now been ordered to enforce social distancing between staff, so that doctors and nurses do not congregate and cause the virus to spread. It is very difficult not to congregate in a hospital setting, so I am unsure how this will work in practice. Meanwhile, the Scottish National Party (SNP) has been accused of hiding the scale of hospital virus outbreaks, with reports that there have been up to 1800 people infected with Covid-19 in Scottish hospitals. This has led to more than 200 deaths. The Scottish Health Secretary, Jeanne Freeman, did at one point say that there had been just 125 incidents of Covid-19 in hospitals, but it later emerged that this figure was actually considerably higher.

No one is doubting the commitment of NHS staff but for many weeks the nation applauded the activities of worthy individuals who were actually, albeit unintentionally, contributing to the disease.